NOVEMBER 2025

Across the rolling hills and wooded valleys of Herefordshire, traces of a once vast medieval network still lie quietly beneath the soil. From the commanding round church at Garway, to the rural holdings at Bosbury and the fortified house at Dinmore, the Knights Templar and later the Knights Hospitaller shaped both the landscape and the life of the county for more than two centuries. These were not isolated monasteries but active centres — commanderies and preceptories— managing farms, mills, and churches whose revenues supported crusader armies and hospitals in the Holy Land. Today, their memory lingers in place-names, field boundaries, and the ancient stonework of churches that once belonged to two of the most powerful orders of the Middle Ages.

SUTTON St MICHAEL – A strategic estate in the Lugg-valley

In the rich agricultural landscape of the River Lugg valley, the parish of Sutton (comprising today Sutton St Michael and Sutton St Nicholas) stood out as a valuable resource for medieval religious-military orders. The Templars, and later the Hospitallers, recognised the potential of the fertile land, generous tithes and pastures of this area.

From Templars to Hospitallers

The church at Sutton, and its associated manor and lands, were originally connected with the Templars. After the suppression of the Templars in the early 14th century their properties passed to the Hospitallers, who managed them as a “member” estate of their commandery at Dinmore, Herefordshire. Sources show that by the late 12th century both Sutton Parishes were confirmed to the Hospitallers via the prior of St Guthlac’s, and by 1185 Sutton St Michael was recorded in their hands.

The parish history states:

“Towards the end of the 12th century, the Priory (of St Guthlac) made over its rights in St Michael to the Knights Hospitallers of St. John to form a large estate controlled from their headquarters at Dinmore.”

Lands and valuations: what the records tell us

From a medieval valuation we know the following about the Sutton estate:

- 200 acres of arable land, valued at 8d per acre.

- 150 acres of arable land, valued at 6d per acre.

- From fixed rents (assize) annual income of 60s 11d (£3 0s 11d).

- From the manorial court (placita & perquisita) annual income of 20s (£1).

- From pasture annual value of 40s (£2).

- From the church of Sutton (appropriated to the Order—in proprios usus) annual income of £10.

- From other small tithes annual income of 34s 1d (£1 14s 1d).

All together the land valuations and incomes totalled £10 8s 4d for the arable alone, and additional incomes thereafter.

This shows the Sutton estate was a significant asset — high-acreage arable, pasture and appropriate church income all combined under Templar/Hospitaller administration.

Why Sutton mattered

- High arable acreage: The large number of acres and relatively good valuations show Sutton was more than a small farm; it was a major manorial asset.

- Church appropriation: The church of Sutton being “in proprios usus” means the Order collected the rectorial tithes directly rather than these going to a local rector. That gave them significant economic advantage.

- Proximity and control: The Lugg valley location was both fertile and accessible, making the estate valuable for food-production, income, and for supporting the broader operations of the Order (whether hospitality, distribution of rents, or strategic landholding).

What remains today

The churches of Sutton St Michael and Sutton St Nicholas still exist in the parish. The medieval landscape may be much altered, but the arc of continuity is visible: parish boundaries, church buildings, and the imprint of monastic/knightly landholding. The conservation area documentation for Sutton St Nicholas notes that both parishes date back to the 12th century and were owned by the Hospitallers.

Legacy and significance

The presence of the Templars (and later the Hospitallers) at Sutton tells us much about how medieval orders organised land, collected rents, and integrated local parishes into broader networks of property and income. Sutton stands out as a micro-cosm of that system: arable land, pasture, tithes, court profits, and ecclesiastical appropriation all feeding into the Order’s finances.

Visitors today to Sutton can look out for the church buildings, the broader parish landscape, and reflect on how this valley once formed part of a network of knightly-religious estates stretching across Herefordshire and beyond to Wales. The fact that the records record values like “8d per acre” or “£10 from the church” gives a tangible sense of how real this enterprise was.

The Knights Templars & Knights Hospitallers at Dewsall, Herefordshire

Tucked into the gentle, arable landscape south of Hereford, Dewsall was one of several small manor-holdings in the Marches that came under the control of the crusading military orders in the Middle Ages.

What the Orders owned at Dewsall

Medieval records and local histories show Dewsall forming part of the Templar/Hospitaller network of holdings in south Herefordshire. In practice this meant the Orders held the manor (messuage) and its demesne, arable land and meadow/pasture, the parish church and its tithes (where appropriated), and fixed rents (rents of assize) paid by tenants. Documentary summaries for the area also record holdings described in carucates (ploughland): for example, Dewsall and neighbouring manors are typically recorded in terms such as two carucates in, c.200 acres, plus rents of assize — the sort of holdings that produced grain, hay and rent income for a distant commandery

Why it mattered: farmed arable and meadow were the principal sources of monetary and in-kind support for the Orders’ activities. The church at Dewsall (St Michael) and any appropriation of tithes strengthened that income stream and gave the Order local influence.

When: Templars → Hospitallers → Dissolution

- 12th–13th centuries: the Knights Templar acquired properties across Herefordshire as part of their English network (administered from local preceptories such as Garway and Upleadon).

- c.1312 onward: after the suppression of the Templars their English lands were largely transferred to the Knights Hospitaller, who ran Dewsall as a “member” estate of a larger commandery (notably Dinmore). The Hospitallers therefore appear in local records from the 14th century onward as the effective landholders.

- 16th century (Tudor period): with the Reformation and the wider dissolution of religious houses, Hospitaller lands were alienated and passed into lay ownership; later centuries saw Dewsall in the hands of local gentry and institutional owners.

Who was present and how the estate was run

The Orders did not normally staff every manor with a large religious household. Typical arrangements for a “member” estate like Dewsall were:

- a lay bailiff or steward appointed to manage the farm and collect rents;

- tenant farmers working strips or holding copyhold tenures;

- a vicar or chaplain serving the parish church where the Order had ecclesiastical rights (if the church was appropriated, the Order took the rectorial tithes and installed a vicar to perform pastoral duties);

- occasional visits from officers of the commandery (Dinmore) to inspect accounts or receive rents.

What remains at Dewsall today

- St Michael’s Church (the medieval parish church) survives and is listed; it contains medieval fabric (the font and parts of the churchyard cross are of medieval date). The church visually anchors the medieval parish.

- Dewsall Court sits near the church; the present sandstone H-plan house largely dates to the 17th century (c.1644) and was later remodelled. The site has long manorial associations (the Pearle family, the Dukes of Chandos, and, for a long period, the Governors of Guy’s Hospital). Much later it has become an exclusive wedding/ events venue and is run commercially today.

Who owns it now?

Dewsall Court is operated as a privately run venue (Dewsall Court Ltd). Historical owners included the Duke of Chandos and, for around 300 years, the Governors of Guy’s Hospital; today the house and business are in private hands and are run as a commercial wedding and events venue.

The Knights Hospitallers at Bolstone, Herefordshire

Nestled west of the River Wye, Bolstone is a small rural parish of scattered farms and cottages, covering just over 650 acres. Today it is known for its mix of woodland and farmland, with Upper and Lower Bolstone Woods forming a county wildlife site managed by rotational coppicing — but beneath this tranquil landscape lies a rich medieval history connected to the Knights Hospitallers.

Hospitaller Holdings

From the 12th century until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century, Bolstone was held by the Knights Hospitallers. The Order, based at the Dinmore Commandery, managed the parish as a small member estate, which included:

- Manorial farmland and pastures — the scattered farms that provided produce and income to the Order.

- Woodland — valuable for timber, firewood, and pannage.

- The Church of St John — an 11th-century building located in the heart of a farmyard. The church’s tithes and lands contributed to the Hospitaller economy, and the Order likely appointed a chaplain or vicar to serve the parish.

The Hospitallers would have overseen the estate through bailiffs or stewards, with local tenants working the land, while the central commandery at Dinmore collected rents, tithes, and agricultural produce.

Transition and Later History

At the Dissolution, the Hospitallers’ lands at Bolstone passed into private hands, eventually coming under the Scudamore family of Holme Lacy. The 17th-century Bolstone Court survives as a reminder of the manorial history, along with several other listed buildings, including Gannah Farmhouse and the tiny Church of St John of Jerusalem, which was restored in 1877 and deconsecrated in 2005.

The Legacy of the Orders

Bolstone illustrates how the Knights Hospitallers integrated into rural England: a small, productive estate, managing farmland, woodland, and ecclesiastical rights to support their wider mission. Today, while the religious presence has vanished, the landscape, buildings, and parish woods provide a tangible link to this medieval chapter of Herefordshire’s history.

The Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller at Harewood, Herefordshire

Nestled in the rolling landscape of Herefordshire, Harewood Park (historically Harewode) carries a fascinating medieval legacy as part of the network of estates once held by the Knights Templar and later the Knights Hospitaller. The estate’s strategic location, fertile farmland, and connection to nearby Garway made it an important source of income and influence for these military-religious orders.

Medieval Holdings and Valuation

Medieval records provide a clear snapshot of the Templar and Hospitaller estate at Harewode:

- Messuage (house with yard/outbuildings): One messuage valued at 5 shillings per year.

- Arable land: 200 acres of farmland at 4 pence per acre, producing a total of 16 shillings 8 pence per year.

- Pasture: Valued at 10 shillings annually.

- Church: The parish church, held “in proprios usus” (for the Order’s own use), brought in 20 shillings per year.

- Woodland profits: Income from the underwood (subboscus) of Garwy and Harewode amounted to 20 shillings per year.

Altogether, the estate combined agricultural, ecclesiastical, and woodland revenues, demonstrating the integrated approach the Orders used to manage their English holdings.

Templar Ownership

The land at Harewood was part of a royal hunting estate, granted by King John in 1215 to the Knights Templar at Garway. At that time, it was already a productive estate with a hall, grange, and chapel. The Templars, whose mission combined military, religious, and economic objectives, would have managed the estate directly through:

- Resident Templar knights or brothers, likely overseeing the estate and representing the Order’s interests.

- Lay stewards or bailiffs to manage agricultural production and collect rents.

- A chaplain or priest serving the parish church, which provided tithes to the Order.

Harewood’s woodland, pasture, and arable fields all contributed to the Templars’ regional income and supported their central preceptory at Garway.

Transition to the Hospitallers

Following the suppression of the Templars in 1312, the estate passed to the Knights Hospitaller, who administered it as a “member estate” of their nearby Dinmore Commandery. The Hospitallers continued to manage the manor, collect rents, and oversee agricultural production. The church and woodland rights remained integral sources of income, while tenants continued to work the land under the direction of the Order’s bailiffs.

Harewood remained under Hospitaller control until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII, when it, like many monastic estates, passed into private hands.

Legacy and Landscape

Today, Harewood Park is part of a Duchy of Cornwall estate, preserving its historic parkland and landscape features. While much of the medieval fabric—such as the original hall, grange, and chapel—has been lost or replaced in later centuries, the estate’s fields, woodland, and place-name echo its medieval role as a Templar and Hospitaller holding. The woodland profits and pasture that sustained the Orders are now part of a managed rural landscape, reflecting centuries of continuity in land use.

Harewood stands as a vivid example of how military-religious orders shaped the countryside: combining religious, agricultural, and administrative functions to manage estates far from their central commanderies, and leaving a lasting mark on the landscape and heritage of Herefordshire.

The Knights Hospitallers at Marstow, Herefordshire

Marstow, a small parish in south Herefordshire, was once part of the extensive network of estates managed by the Knights Hospitallers. Though the Order’s presence here was modest compared to larger preceptories, their holdings reflect how they integrated into rural England, managing farmland, woodland, and ecclesiastical rights.

Location and Landscape

The Hospitallers’ site at Marstow is believed to have been along or very near Garron Brook, in the floodplain southwest of St Matthew’s Church at Brelston Green. On historic maps, the point SO 550190 (~51.8677 N, -2.65499 W) marks the location of the old church associated with the estate.

Evidence of the medieval landscape survives in:

- The churchyard wall and the base of an old churchyard cross.

- A footbridge over Garron Brook, near what sources describe as the path past the old yard.

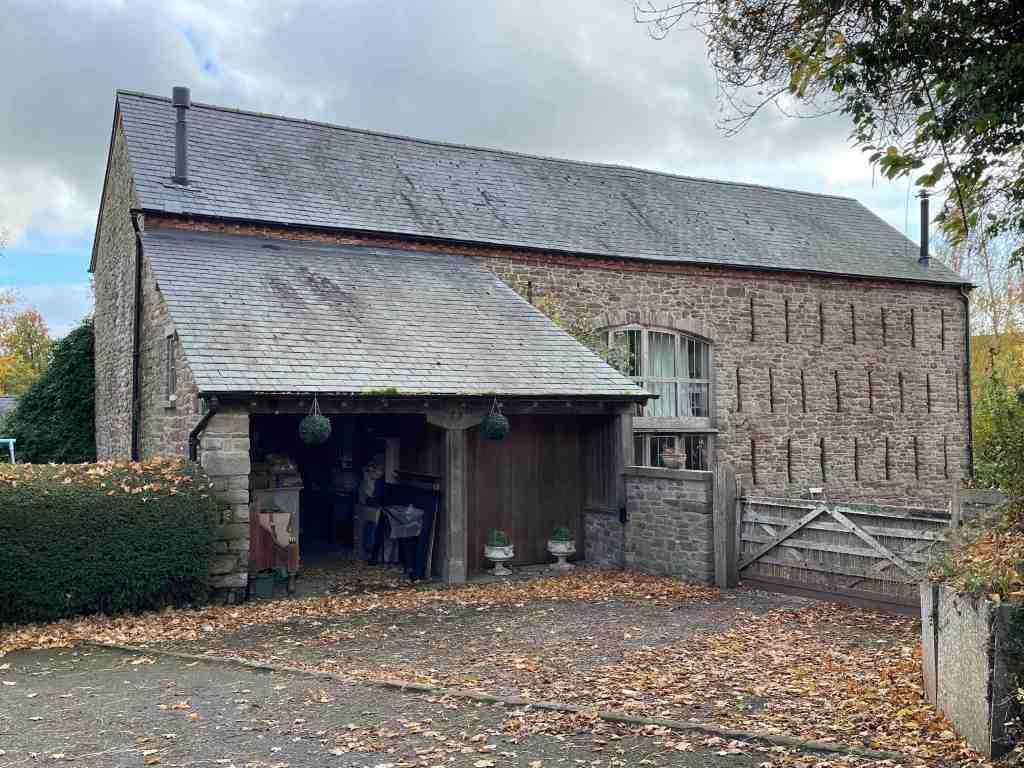

- The nearby listed out‑building, formerly a granary, about 30 yards east of Marstow Court, reputedly associated with the manor of the Knights Hospitallers.

Land and Property

Although precise medieval records are scarce, the estate likely included:

- A manor farm or grange, where agricultural produce was collected and stored (as suggested by the granary).

- Arable land, pastures, and possibly woodland, managed by tenants and overseen by a bailiff or steward appointed by the Order.

- Ecclesiastical rights linked to the local parish church, with the Order receiving tithes and appointing a chaplain or vicar to serve the community.

The estate would have operated as a “member” property of the nearby Dinmore Commandery, forming part of the Hospitallers’ wider economic and administrative network in Herefordshire.

Legacy

Today, very little remains of the medieval Hospitaller estate, but the landscape retains subtle traces: the churchyard wall, the base of the cross, and the granary building at Marstow Court all hint at its past. These features, alongside historic maps and the surviving floodplain of Garron Brook, help preserve the memory of the Order’s presence in this corner of the English countryside.

Marstow illustrates how the Knights Hospitallers combined religious, agricultural, and administrative roles, even in smaller rural estates, leaving a footprint that can still be traced in the historic landscape.

The Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller at Kemeys Commander, Monmouthshire

Kemeys Commander, a small hamlet in Monmouthshire, preserves a fascinating medieval legacy in its very name. The term “Commander”signals its past as the site of a commandery or preceptory of the Knights Templar, later passing into the hands of the Knights Hospitaller after the Templars’ suppression in the early 14th century.

Medieval Holdings

Records from the period provide a snapshot of the estate’s wealth and structure:

- Messuage (manor house): One house or homestead, valued at approximately 5 shillings per year.

- Arable land: 120 acres, valued at 3 pence per acre, contributing to the estate’s overall income.

- Church: The parish church at Kemeys was held “in proprios usus” — in the personal use of the Order — bringing in an annual income of 2 shillings.

- Total valuation: 30 shillings per year.

This modest yet productive estate would have included a manor farm, surrounding fields, and the parish church, which the Order used to appoint clergy and collect tithes.

Administration and Residents

Under the Templars, Kemeys Commander likely hosted:

- A preceptor or Templar brother overseeing the estate and representing the Order.

- Lay stewards or bailiffs managing day-to-day agricultural production.

- A chaplain or vicar serving the parish church, which provided tithes directly to the Order.

After the suppression of the Templars (c. 1307–1312), the estate passed to the Knights Hospitaller, who continued to collect rents, manage farmland, and oversee ecclesiastical income. Surviving records indicate that the Hospitallers drew around £2 13s 4d per annum from the demesne lands at Kemeys Commander.

Location and Landscape

The estate was located along the bend of the River Usk, near the present hamlet, forming part of the fertile and strategically valuable Marches borderlands. The surviving All Saints Church is a Grade II* listed building, dating in part to the 13th–14th century, a tangible reminder of the Order’s presence. Other landscape features, including farm buildings and the name “Commander” itself, preserve the medieval footprint of the estate.

Legacy

Though the Templars and Hospitallers have long vanished from Kemeys Commander, the hamlet retains its historic character. The combination of church, manor, and farmland illustrates the typical pattern of rural estates under military-religious orders: modest in size but carefully managed to support the broader activities of the Order in England and Wales. Today, visitors can see the surviving church, trace the manorial layout, and appreciate the centuries-old link between landscape and the Orders that once held it.

The Knights Hospitallers at Oxenhall: A Forgotten Medieval Estate

Tucked away just south of Newent on the Gloucestershire–Herefordshire border lies the quiet parish of Oxenhall. Today it is a peaceful rural community of farms, orchards, and woodland — but in the Middle Ages, Oxenhall formed part of a major network of lands owned by one of the most powerful organisations in Christendom: the Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, better known as the Knights Hospitaller.

🕍 How the Hospitallers Came to Oxenhall

The origins of their presence go back to the late 12th century, when the Devereux family — local Marcher barons — granted the church of Oxenhall with its glebe lands to the Hospitallers. From that point onward, the order held:

✅ The rectory and church tithes

✅ Four bovates of glebe land (around 60–80 acres) surrounding the church

These assets formed part of the Bailiwick of Dinmore in Herefordshire — one of the order’s most important English commanderies, supporting its work in the Holy Land.

📜 Recorded in the 1338 Survey

The most detailed surviving record of the estate appears in the 1338 report of Hospitaller Prior Philip de Thame. Here, Oxenhall is listed as:

“Ecclesia de Oxinhale, cum iiij bovatis terre ad firmam … xl s.”

The church of Oxenhall, with four bovates of land let to farm at will: 40 shillings annual income.

This tells us that the estate was productive and valuable. Though small compared to the grand houses of the order, it played its part in financing crusader defences and the order’s growing medical and charitable missions.

✝️ Templars vs Hospitallers?

There is no firm evidence that the Templars ever held property at Oxenhall.

Instead, the estate appears throughout the medieval period as exclusively Hospitaller.

However, after the Templars were suppressed in 1312, many of their English lands passed to the Hospitallers — which may help explain local memory sometimes linking both orders with Oxenhall.

🏰 What Stands Here Today?

The most visible medieval legacy is St Anne’s Church (originally St Mary’s), which occupies the same church siterecorded in 1338. Though restored in 1866, it preserves earlier medieval fabric — the physical footprint of the Hospitallers’ holding still rooted in place.

The glebe lands — the four bovates — can still be traced in the field patterns around the church. Parish boundaries today reflect the same estate footprint that once supported the order’s mission overseas.

🧭 A Quiet Parish With a Global Connection

It’s easy to overlook a small village like Oxenhall when thinking of the great crusading movements of the Middle Ages. Yet this modest church and its farmland plugged into one of Europe’s largest land-owning networks, with money from Oxenhall flowing — quite literally — to Jerusalem, Rhodes, and Malta.

A reminder that even the quietest English parishes once played a part in shaping the medieval world.

Learn More about the Knights Hospitallers in the UK on our main website by clicking here

Check Out out Knights Gift Store for your replica Knights Templar, Hospitaller and Order of St Lazarus Armour, weapons clothes & gifts by clicking here