JANUARY 2026

In the Middle Ages, long before Clerkenwell became part of the dense urban fabric of London, it was the headquarters of one of the most powerful religious and military orders in Europe: the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem.

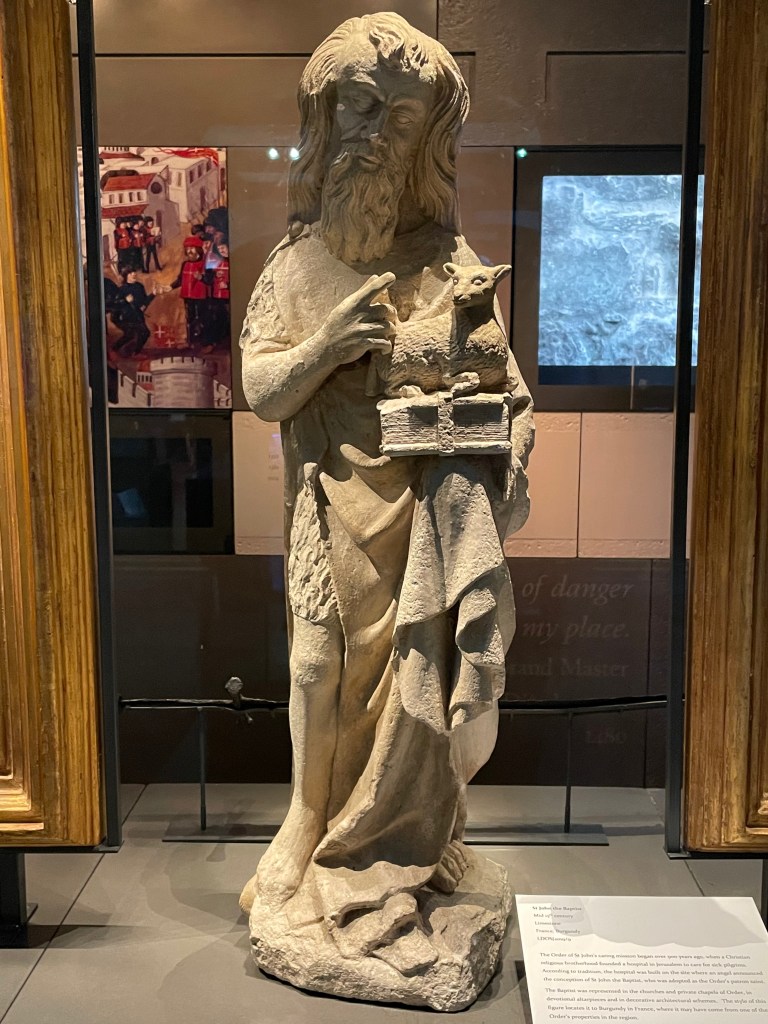

Founded during the Crusades, the Hospitallers began as a charitable brotherhood dedicated to caring for sick and injured pilgrims travelling to the Holy Land. As conditions grew more dangerous, the Order gradually took on a military role, defending Christian territories while never abandoning its core mission of hospitality and medical care.

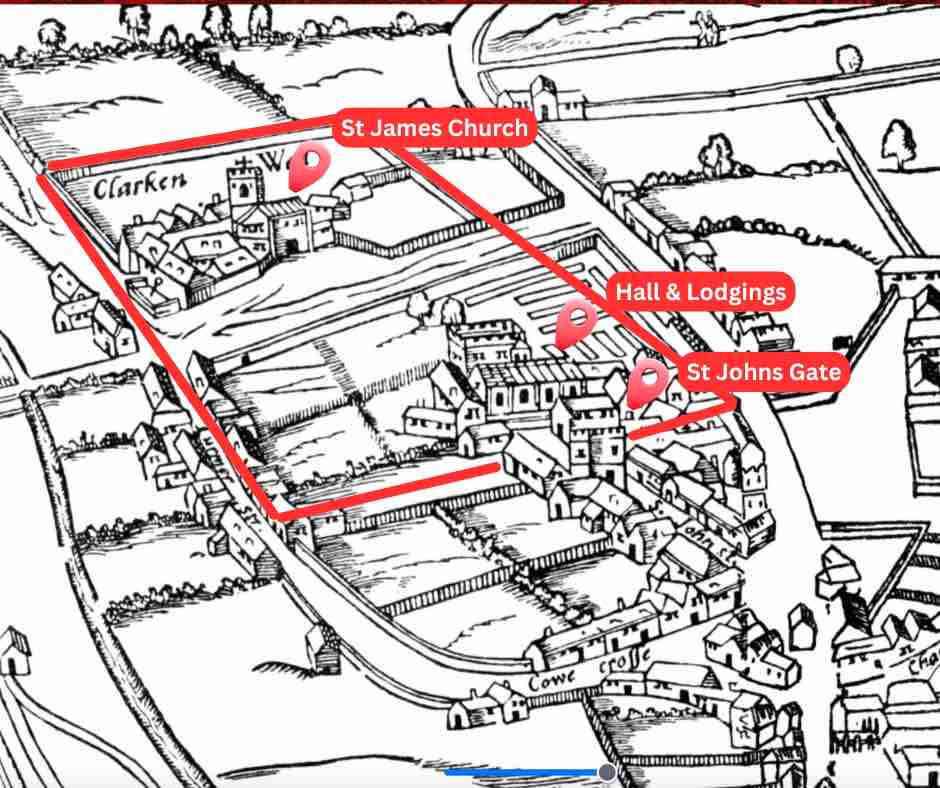

A Rural Site Beyond the City Walls

The Hospitallers’ association with Clerkenwell began in 1144, when their English headquarters – known as a priory or preceptory – was established just outside the medieval City of London. Although Clerkenwell today lies close to the city centre, in the 12th century it was a rural landscape north of the city walls, bordered by fields and meadows and lying close to the River Fleet. Nearby was the Clerk’s Well, a natural spring that gave the area its name.

The location offered space, fresh water, and access to major roads, making it ideal for a large religious and administrative centre. The Priory at Clerkenwell became the residence of the Grand Prior of England, firmly establishing it as the administrative heart of the Order’s English lands.

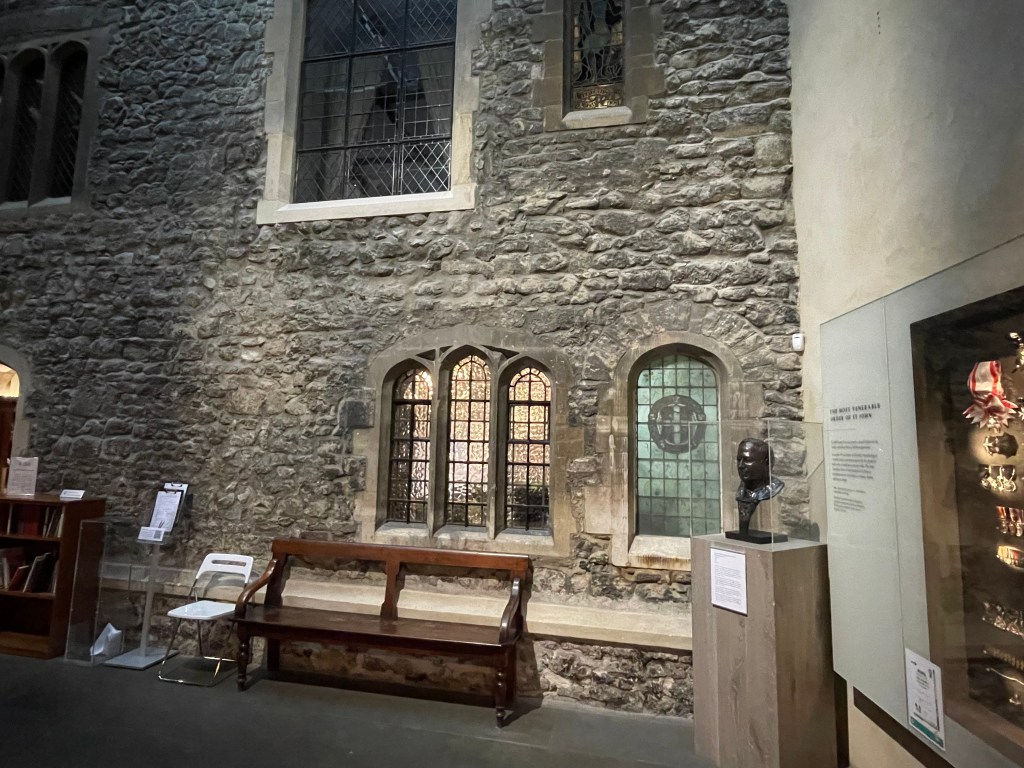

The Priory Church and Its Crypt

The earliest surviving part of the Hospitallers’ complex is the crypt of the priory church, probably the first structure built on the site. Above it rose a striking church with a circular nave, deliberately designed in imitation of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Completed around 1160 and consecrated in 1185, the church symbolically linked Clerkenwell with the spiritual centre of Christendom.

Although the medieval church no longer survives above ground, its footprint is still marked today in St John’s Square, where paving traces the outline of the circular nave and helps visitors visualise the scale of the lost building.

A Self-Contained Priory Complex

Over time, the Clerkenwell priory grew into a large, self-contained monastic and knightly precinct, covering several acres. While no complete medieval plan survives, archaeological evidence and historical descriptions allow a good understanding of its layout.

At the heart of the complex stood the church, surrounded by a rectangular cloister roughly corresponding to the present St John’s Square. Around this were ranged the essential buildings of the community:

- Dormitories for the brothers

- A refectory (dining hall)

- A chapter house for meetings and governance

- A Hospitaller infirmary

- Guest accommodation for pilgrims and travellers

- Kitchens, workshops, and storage buildings

Beyond the inner precinct lay an outer estate, with land and properties leased to tenants, craftsmen, and servants. Evidence suggests the priory extended roughly from St John Street in the east, westwards towards the River Fleet, and north towards St John’s Path and the Aylesbury Street area. This made Clerkenwell a prestigious and economically significant estate, well connected to London’s markets and roads.

Clerkenwell in 1338: A Centre of Wealth and Authority

A vivid snapshot of Clerkenwell at its height is provided by a detailed Hospitallers’ survey of 1338, which described the priory as:

“The principal manor of the entire Priory of England.”

This survey reveals not only the scale of the estate, but the extraordinary range of lands, rents, and rights that sustained it.

At Clerkenwell itself, the report records a principal manor, including a garden and a courtyard, valued together at 20 shillings. From this centre flowed extensive revenues, including:

- Rents from assizes and foreign rents, worth £40 per year

- The friary of Middlesex, London, and Surrey, valued at 40 marks

- One fulling mill, worth 20 shillings, reflecting involvement in the cloth trade

- Two water mills, rented for 100 shillings, providing reliable income

- Eight acres of land, valued at 15 pence per acre

- Forty acres of meadow at Waltham, valued at 2 shillings per acre

- Eighteen acres of meadow at Aylsicroft, also valued at 2 shillings per acre

- Pleas and perquisites of the courts, worth 40 shillings, derived from manorial justice

- Revenue from Assch in Kent, amounting to £4 per year

- The church of Thurrock, appropriated to the priory and valued at £10 per year

These holdings show Clerkenwell as not merely a religious house, but a major economic enterprise, managing agriculture, industry, rents, and legal authority on a substantial scale.

The Brothers of Clerkenwell

The same 1338 report also records the brothers resident at Clerkenwell, offering a rare insight into the people who lived and worked at the heart of the Order’s English operations.

Those present included:

- Brother Nicholas of Hales, Prior of the church, responsible for spiritual leadership and governance

- Brother Hugh of Lichfield, Chaplain

- Brother Walter of Wenge, Chaplain

- Brother Thomas of Bredstrete, Chaplain, ensuring the continual round of worship and pastoral care

- Brother Alan Macy, Preceptor (Commander of the House), overseeing daily administration and estates

- Brother John of Thurmeston, Claviger (Keeper of the Keys and Treasurer), responsible for finances and secure stores

- Brother William Brex, Knight, representing the military character of the Order

These men formed the senior core of the priory, supported by a much larger population of lay servants, artisans, labourers, and dependants.

Life at the Priory

Clerkenwell was a busy and diverse community, combining religious devotion with practical and charitable work.

Daily life followed a disciplined rhythm of prayer and worship, interspersed with meals taken communally in the refectory. The care of guests, pilgrims, and the sick demanded constant attention, reflecting the Hospitallers’ founding purpose. Alongside this ran the complex business of estate management, legal administration, and financial oversight.

Although England itself was far from the battlefields of the Crusades, Clerkenwell played a vital role in recruiting and hosting knights, organising correspondence, and coordinating with the Order’s senior command overseas.

Destruction, Survival, and Legacy

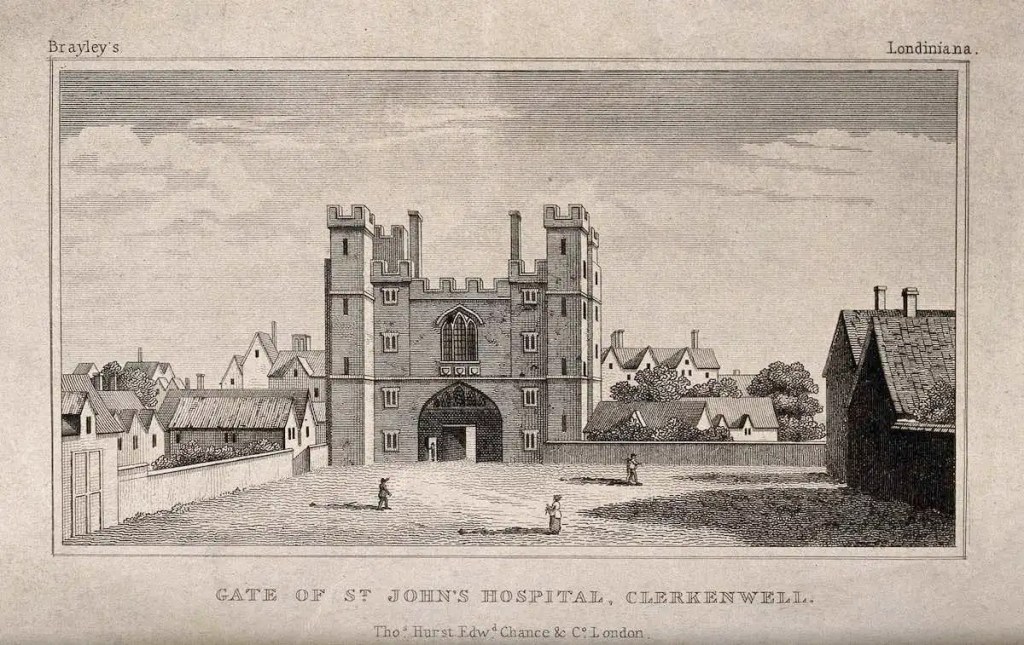

The priory suffered severe damage during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, when much of the complex was burned by a mob. Although it was rebuilt and continued to function, its fate was sealed in 1540, when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries and seized the Hospitallers’ property. Most of the buildings were demolished soon after.

Yet important traces remain. St John’s Gate, the sole major surviving medieval structure, still stands today and now houses the Museum of the Order of St John. Beneath the modern church of St John Clerkenwell lies the medieval crypt, while the outline of the great circular church is marked in the paving of St John’s Square.

Clerkenwell Remembered

For nearly four centuries, Clerkenwell was a centre of charity, power, and international connection. Though much has vanished, the surviving buildings, buried remains, and detailed records such as the 1338 survey allow us to reconstruct a place that was once the beating heart of the Knights Hospitallers in England — a community where prayer, care for the sick, and the management of a vast estate shaped everyday life.

Learn More about the Knights Hospitallers in the UK on our main website by clicking here

Check Out out Knights Gift Store for your replica Knights Templar, Hospitaller and Order of St Lazarus Armour, weapons clothes & gifts by clicking here